The Sea In The Metro

by Jayne Tuttle

Hardie Grant Books 2025 277pp

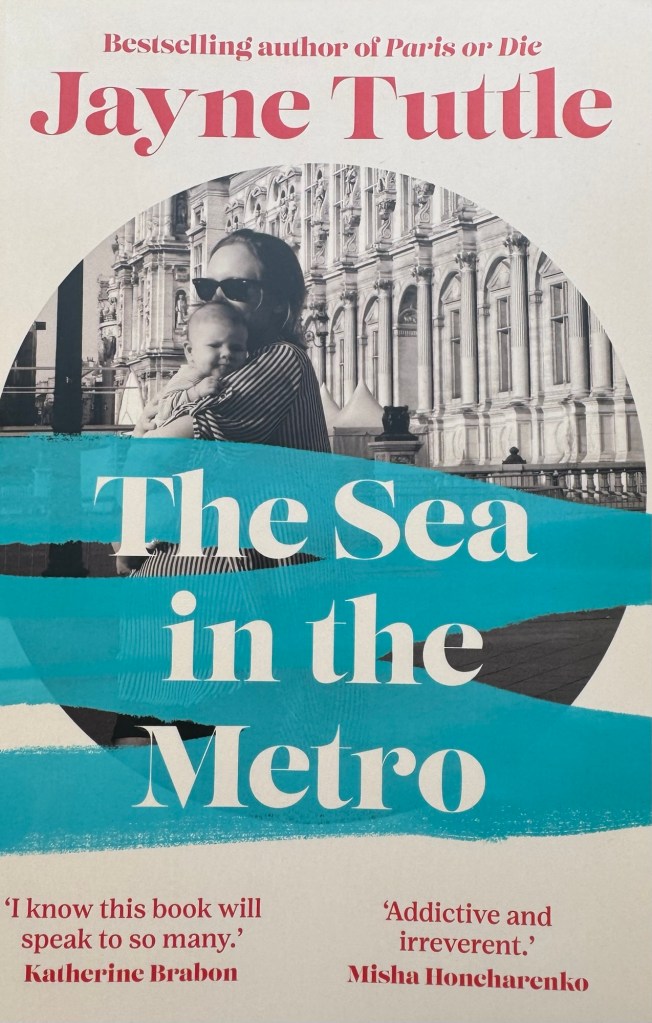

The cover of this book intrigued me. There’s a greyscale photo of a mother in sunglasses, facial expression obscured by her somewhat underwhelmed baby, with a European facade behind them.

Ok, mum and bub on the other side of the world, possibly not having a good time. Mum hiding? Bub holding on to Mum’s sleeve, looking cautious, uncertain of what’s next, maybe?

Sensible baby! Because what’s next is….several brushstrokes of turquoise cross the lower half of the photo! Then the title one might expect to make sense of all this is imposed on this splash of colour: The Sea In The Metro.

What? This is absurd! Paris’ underground railway containing sea, the nearest of which is 170km away? (I checked). This makes no sense! It’s like a piece of experimental dance theatre or something.

Which figures. Jayne Tuttle, the author of this third instalment of memoir, first went to Paris as a young woman to study theatre. This book – which I found fine as a standalone, not having read the first two – describes some of the experimental work she’s been involved in.

I wondered what it was like in the audience at those gigs. What state do you have to be in to roll with the absurdity you’re witnessing? What if it’s all a bit much and you want to run from the theatre?

I’m not sure I could have handled it while my kids were little and I wasn’t getting sleep or you know, out much. But now they are all bigger, I could really imagine being challenged by this kind of art, especially as it’s described here.

Tuttle writes like a dancer, knowing when words work conventionally, and when they need to move around like a body through space and time. If anyone’s equipped to approach the absurd – something as weird as the metro having the sea in it, from an acting school mental exercise – it’s her. Especially when tackling the absurdities – and their polar opposites, the meanings – of the main subject of this book.

Ah yes, the main subject. Don’t be fooled, this book isn’t really about Paris or France. Yes, it’s about living somewhere else for a while. Yes, it’s utterly immersed in Frenchness, – la mère dans le Métro! – but that’s not the language it most importantly speaks.

France is not where this story really comes from.

Granted, the evocative foreign location this book is about is definitely a lot like Paris: somewhere everyone recognises and therefore thinks they know; treasured and trashed in roughly equal measure; full of beauty and frustration and anxiety and bad smells and intoxicating moments that make it worthwhile.

Until the next hellish challenge of life there, where they do things differently. If an English book once convinced us the past is a foreign country, then this Australian book suggests that early parenthood is a foreign country too.

Once you’ve lived there, you never really leave.

Following Tuttle and her husband and daughter through these chapters I was reminded of the journeys of so many mothers and fathers and their little ones. Most of them were in Melbourne where I practice perinatal and parenting psychotherapy, but some were in other cities or regions.

All – thanks to what our culture does to parents in the early years – found themselves trying to make life work somewhere foreign, immersed in a culture and language that felt familiar but at times also quite out of reach.

Somewhere they’d known about all their lives, heard about from people who’d been there, met people who’d lived there even. But they couldn’t really know how they’d find it until they’d lived there themselves.

That this metaphorical migration occurs during a literal migration for Tuttle and family means the two are entwined, superimposed at times, magnifying the disorientation, heightening the sense of the absurd.

Birth experience plus Frenchness; Lack of family support plus Frenchness; Separating for childcare and school plus…Frenchness.

Our nervous systems make meaning for a living. If they get overwhelmed, things around them can seem absurd. It’s common for people who’ve experienced trauma to struggle with the absurdity of their fragmented memories. Long before we had Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) and other evidence-based trauma treatments, we had art to wrap itself around our fragments, make meaning when we couldn’t.

Which makes me wonder about that title. Is parenting plus Paris, like Sea plus Metro? An absurd collision, it’s the artist’s job to make sense of?

Well that’s the idea, maybe. But this book is a knife-edge journey for much of its length. Tuttle works harder and harder at her paid employment to stay afloat in an underground tunnel flooded with saltwater, and it’s not clear if the needed buoyancy is just financial or existential.

Who is she doing this for? She’s not sure, but she tells us as much. Her flinching but insistent commitment to honesty is disarming enough to build trust in the writing. To go down into the tunnels with her.

The toddler in this book is called The Chunk. At first I worried (as I worry about these things for a living) that it might be a bittersweet backhander of a nickname, the kind of which very stressed parents give a child who’s taken a chunk out of them.

I was totally off course on that one. The Chunk got named by her creatively fidgetty wordplaying parents from Chunk of Love, and is clearly adored.

I believe this because Tuttle goes to hell and back more than once for her daughter.

She doesn’t hide from us the ugliest things a mother can think or feel, and this means that when she does arrive at moments of seeing The Chunk’s beauty it’s entirely credible.

Credible statement: Paris is beautiful. And messy and noisy and it’s a nice place to visit but another thing altogether to live there.

Credible statement: Children are beautiful. And messy and noisy and wherever they live is a nice place to visit. But it’s another thing altogether to live there.

How do you do justice to these contradictions?

The Sea In The Metro chooses this battle like a parent with a toddler torn between play and sleep, and doesn’t give up trying to resolve it. Only in the acknowledgments is there a sense that the writing of this memoir delivered some peace for Tuttle, and I love that, that there’s no neat ending. It gives dignity to all the readers who’ve fetched up in some foreign country in their lives, be it through parenting or some other migration.

Tuttle lived for so long in two foreign places at once, pulled between parts of herself that were crying out for more, while trying to be more for her preschool daughter and frustrated musician husband.

She was stretched so thin as to seem translucent in her writing, and because it didn’t kill her we can now appreciate in comfort the light show of her, illuminated by the combustions of that perilous state.

Tuttle’s writing also illuminates her little household so vividly. Both The Chunk and M have moments where the camera adores them in their fragility, earnestness and warmth. I’m a Fatherhood Clinician and love to see men well-represented as caregivers. M is a role-model for dads, especially creative dads struggling with the double disenfranchisement of male caregiving and creative industry, both of which are undervalued and underpaid in our wacky world, in Australia as well as in France.

My anticipated deathbed regret list has for decades had ‘never lived in a foreign country’ on it. Also ‘studied French for 7 years at school, never lived in France.’ I feel a bit like I have lived in Paris now, though I know there’s no substitute for the real thing. There’s still time, right Jayne?

But what this book gave me more of was the sense of the weird and wild places the early parenting years take you, what you have to fight for there, and why it’s worth it.

#psychiatrying